What I learnt as a guy in a pole studio

I fretted about being the only male in my pole classes. Did I need to?

“I notice, umm, most of the people in this studio are women,” I remarked to the sales manager of a local pole studio. “How will I fit in?”

“Most” was an understatement. I’d already felt out of place just walking up their driveway. And I wasn’t even interested in pole—I wanted to work on my flexibility, and it turns out that pole studios run stretch classes, without the fluff accompanying yoga. So here I found myself, wondering if they could help.

The sales manager assured me I’d be welcome (“so long as you’re, like, a good person!” she added nonchalantly, seeing my dubiousness), and I signed up to two classes a week. I still had doubts, but there was only one way to know for sure.

“What is it with boys and not replacing their socks?”

The start was uncomfortable, and I continued to question if I was allowed to be there.

I mean, the whole space felt female-oriented. Guidance for stretch classes recommended “leggings”. There was just a single toilets area. The studio’s colour scheme was pink. Instructors seemed used to talking as if their classes were all female and (mostly) caught themselves just in time. One made a comment about the holes in my socks and how boys don’t replace them.

Did I mention that I was the odd one out? Weren’t partner stretches bound to be awkward?

Well, maybe. But a subtle shift in perspective can help. Leggings aren’t necessary and not everyone wears them. Pink’s not my thing, but it’s only a “girl’s” colour if you want it to be. If instructors were catching themselves, it’s probably because they cared enough to. If stretch partners showed signs of hesitance, I couldn’t tell you what they were. And that socks remark? In any other context, it would’ve been just a friendly joke!

Everything just felt a little exaggerated when I was hyperconscious about being in the minority.

This ran the other way, too. In my second month, the studio’s student of the month was male. I’d never met him, he was clearly more athletic than me, and I had no reason to believe his experience would mean anything for mine. But it somehow felt like the studio’s recognition of him legitimised my existence.

Even seeing different ages and body shapes made my presence feel somehow more acceptable. But those have nothing to do with gender! It doesn’t make any sense!

“I’m very excited to have you in my level one class!”

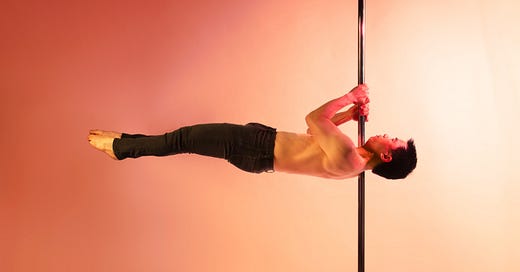

The enthusiasm and work ethic in the studio were contagious, and six months later—to the excitement of my instructors—I started pole classes proper.

New questions quickly arose. Some were practical. What do I wear? Beginners use just hands and knees, so t-shirts and shorts were fine at first. But it doesn’t take long to get to thigh grip, and instructors started suggesting rolling up my shorts. Where would I find shorter ones? Men’s sportswear doesn’t normally go shorter than a 5-inch inseam. I had some 2½-inch running shorts, but their bagginess got in the way. Polewear stores’ men’s sections had barely one or two items, if any at all. My instructors, all women, wouldn’t know the answers, would they?

Also, holding a pole with your thighs is painful, and this seems to be true for everyone. But for me it was excruciating, and I’d watch classmates learn to cope while I still couldn’t handle it. Was the hair on my thighs to blame? Most women shave their legs anyway, poler or not, so it was probably never a question for them. The two other men were in advanced levels, so I never crossed paths with them, and anyway, I’d have been too shy to ask something so personal.

I eventually took the plunge, and my newly shaved thighs reduced the pain from impossible to bearable. An instructor noticed the sudden progress and I explained the change. “Yes!!!” she motioned for an overexcited high-five, as an amused classmate’s head turned. Months later, I’d hear another instructor say in passing that they normally don’t mention shaving, to try to be “inclusive”. Fair enough, though I wouldn’t have minded the practical advice.1

Another question was more philosophical. Do I feel more included when my differing gender is acknowledged, or not mentioned?

I didn’t really want to be singled out. But when one instructor said to me that she’d seen men on average fare better with strength and women with skin pain tolerance, it was reassuring—maybe my struggles weren’t so unusual.2 Then again, when another instructor called out “male advantages” in strength moves during class, it landed differently. Sure, physiological factors probably helped, but I worked really hard for many years before pole to build that strength!3 Later, when instructors started encouraging me to perform in a showcase, citing the value of having more male representation, I couldn't decide whether I felt heartened or tokenised.

I always used to wonder how women in my engineering classes felt about explicit gender mentions. Now here I was, on the other side of it. I wish I could say that experiencing the receiving end myself shed light on the answer. Alas—the tension between fitting in and navigating differences is not so easily resolved.

“If they can do it in their careers, I can do it in a hobby”

I'd be lying if I said I never questioned whether it was worth the discomfort. But something kept me going: my past life as a teaching assistant in engineering courses.

In that role, I'd spent no small amount of thought on how women felt in my classroom. I knew the statistics on gender representation, and I'd heard many stories from female colleagues about their experiences. To be clear, engineering and pole are of course different contexts in many ways—for starters, my new pastime is not my profession. But there is one important parallel: the gender imbalance, just in reverse. So, I kept telling myself: if they can navigate being a minority in their careers, surely I can handle it in a hobby?4

Recognising this helped me keep some perspective. Whenever I questioned my place in pole, I could look back at my engineering experience and ask: how do I behave when I'm in the majority? Most of the time, I realised, you don't notice how behaviours that feel perfectly natural might feel different to someone in the minority. With polers, this helped me take some uncomfortable moments more lightly.

I remembered a conversation from an engineering journal club, where a colleague recounted how wearing a simple work dress prompted questions about whether she had a date that evening. At the time, I was surprised by how much weight she placed on this seemingly casual interaction, going as far as to never wear a dress to lab again.5 But now, I could relate to how such moments can take on outsized significance—just as I now found myself overanalysing every interaction in the studio.

The challenges of gender diversity in STEM fields are complex and substantial, spanning systemic barriers, implicit biases and sometimes overt discrimination. But my experience in pole showed me one more element: simply being in the minority can colour your perception of otherwise everyday interactions. Even in a welcoming environment like my pole studio, I started to see how this dynamic could make me interpret neutral signals as loaded ones.

“Because it’s more masculine?”

As the months passed, the gap between my initial anxieties and my actual experience became increasingly apparent. That sales manager’s assurances held water; the community I had joined lived up to them.

So I found myself wondering: Why did they let me in? Why do polers not only accept men in their ranks, but actively cheer them on? Wouldn’t a guy in their not-very-clothed space raise suspicion? In a world where most sports are male-dominated, wouldn’t they want to keep this one for themselves?

I think it’s much simpler. When people love what they do, they want to share it with everyone. I’ve seen it elsewhere—ballerinas I know wish more boys would join in; engineers I know say the same for women. There’s something almost uniquely disheartening about watching someone turn away from your passion just because they feel they don’t “look like” the others.

In a pole studio, polers are polers first, and everything else second. They love what they do, and they want you to love it too. Naturally, to some individuals, the hobby will mean something personal to a part of their own identity. But otherwise, the fact that you’re poling is all that matters. Anything else about you is kind of beside the point.

For my part, I try to keep it all beside the point too. People shouldn’t fuss about whether something is a “girls’ thing” or a “boys’ thing”. They should just do things they think are cool. I think pole is cool, so I continue to show up. It’s challenging, rewarding, and has scores of people to aspire to. With its plethora of substyles, from athletic power moves to mesmerising spinning shapes to gooey sensual flows, different people will find different things in it for them.

A few months in, I started to discover this diversity more fully on pole Instagram, where I found a small but notable presence of male polers. After class one day, while chatting about how I was gravitating towards dynamic, acrobatic tricks, an instructor gave me a knowing smile.

“Because it’s more masculine?” she suggested.

Touché. I guess some tastes resist philosophical scrutiny.

Addendum

I first drafted this two years ago, when I was about a year in. But things got busy, my original draft didn’t sit right, and I let it slip.

Since then, I've navigated a ten-month wrist injury, performed in my first showcase, and made a lot of progress. Countless instructors have inspired and guided me along the way, and I’m indebted to them for their support.

I didn’t originally expect to make friends at pole. (“Do you not normally get along with women?” asked my bemused therapist.) Turns out if you spend long enough with like-minded people trying to do like things, eventually friends you become, and I’m grateful to have them.

I’ve learnt a small amount about strippers’ work, from a few in the pole fitness scene trying to bridge the gap between the two. I had no prior conception of their world. Their perspective is worth knowing and I appreciate them for sharing it.

And that flexibility I originally signed up for? That improved a lot, especially in my first year. I’m happy to report that I can now touch the floor with my palms and sit in a straddle without falling backwards. But as I progressed in pole, the goalposts shifted; some moves demand a level of mobility that remains elusive. No one promised it’d be easy! So the journey continues.

After ten months off for an injury, I retried the experiment, this time with one hairy and one shaved thigh. This was much less conclusive. I couldn’t detect much difference in direct immediate pain levels, but I still felt less hesitant about launching myself into moves with shaved thighs. Maybe it was all in the mind.

The instructor gave the standard generalisation disclaimers, of course. It’s hard for me say how well it holds myself—I haven’t since heard anyone else say this, and I have heard of others struggling with pain tolerance too.

Also, plenty of my (female) classmates bias towards strength over flexibility too. It seems to depend on the person; I’d guess partly prior fitness background and partly different bodies being different.

Actually, my brain went further. If I quit because of it, how would I ever say to my female engineering students that they should stick around?

I also didn’t understand how her labmate got from “dress” to “date” in the first place, so I can understand her perplexed reaction.